Among Creatures: Orcas, Humans and Conscious Life

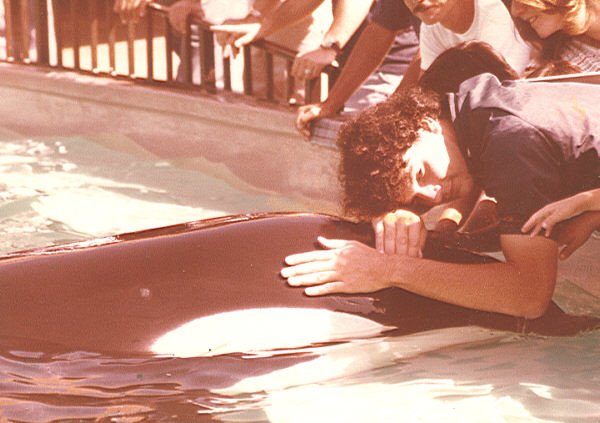

From the archives of photos taken by biologist, Robyn Waayers, during her visits to the petting pool: Young Kotar seen moving calmly beside adults and children, a moment suspended between innocence and impossibility. SeaWorld San Diego, 1980.

Among Creatures: Orcas, Humans and Conscious Life

By Robert Anderson

with Désirée Braganza, Everyday Ethology

And now we welcome the new creature,

not yet known to us,

and we begin to know ourselves

only through the eyes that meet ours.

- adapted from Rainer Maria Rilke, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge (1910)

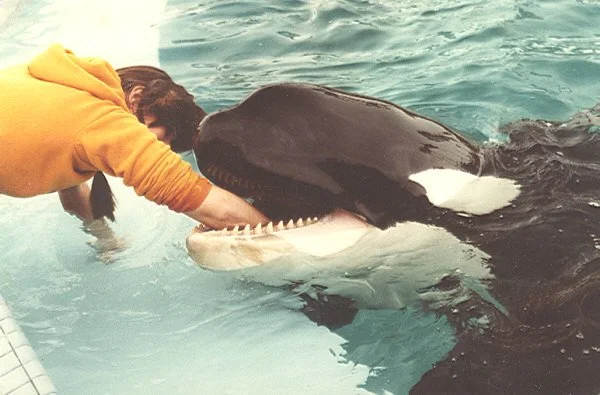

Kotar approaching Robyn Waayers in a friendly manner, making eye contact.

Introduction: Meeting the New Creature

Robert Anderson is an astrophysicist whose career included building satellites for NASA deep-space missions, particularly their onboard control computers. These spacecraft must operate with real autonomy because signals between Earth and a craft near Saturn can take more than an hour each way. They have sensor “eyes,” articulated “arms” and a computer “brain” to interpret their environment and keep themselves safe. Robert’s training also introduced him to exobiology: how life and minds might evolve elsewhere.

Shortly before starting on his first deep space mission, Robert had become friends with four orcas. He got to explore via physical interactions and socializing, fascinating non-human minds, separated from us in evolution by tens of millions of years. This was possible because SeaWorld San Diego kept four newly captured orcas. Two were placed in the dolphin petting pool while the other two were in training. Perhaps two dozen visitors out of thousands formed friendships with these orcas. A few of these visitors connected on the internet decades later.

Robert has spent the years since contemplating the mind: artificial, non-human and human.

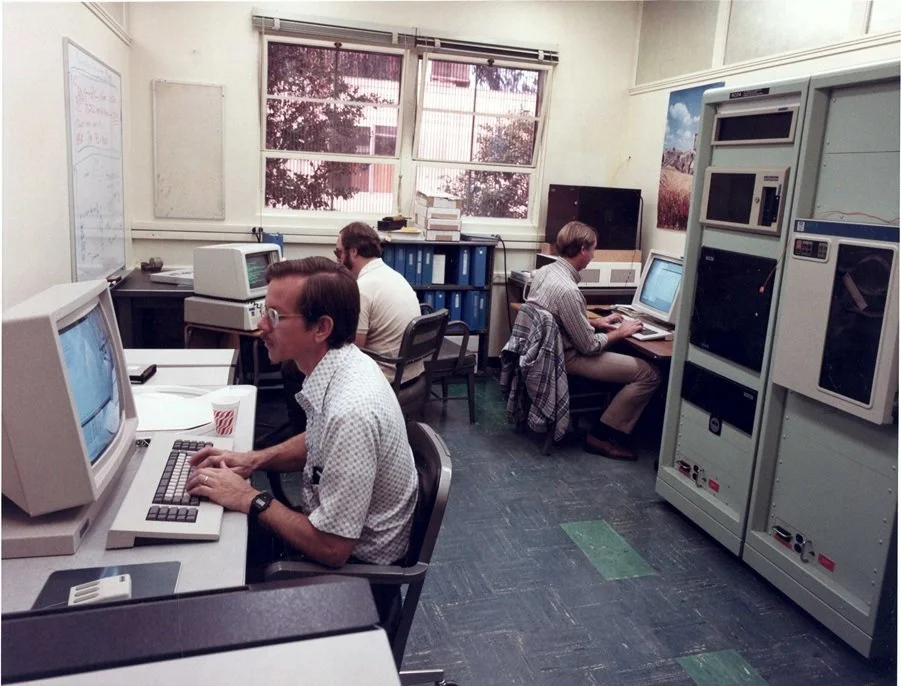

Photo: Robert (left), whose improbable orca days were already behind him, now immersed in writing software for Ground Support Equipment (GSE) for Magellan, headed to Venus. It provided a human interface, that an operator sitting at the GSE could use to talk directly to the satellite computer.

Our Collaboration

Earlier this year we co-authored Horses, Orcas and Morality. The response from scientists, artists and readers of both species has been deeply moving. The article has now reached twenty-three countries.

What follows is a conversation that grew out of reflections of that piece. It moves more deliberately into questions of consciousness, experience and recognition. We focus on orcas, yet the pathways extend to all mammals: equine, bovine, human and beyond.

This is a dialogue, not a debate. The ideas emerge from lived experience and long practice. Robert kept his state-of-the-art camera away from the water and did not take photographs during his visits, but some of the images shown here were taken by visitors who found one another again years later through shared memories. Additional photographs from other eras and parks help provide context. Further readings are listed at the end.

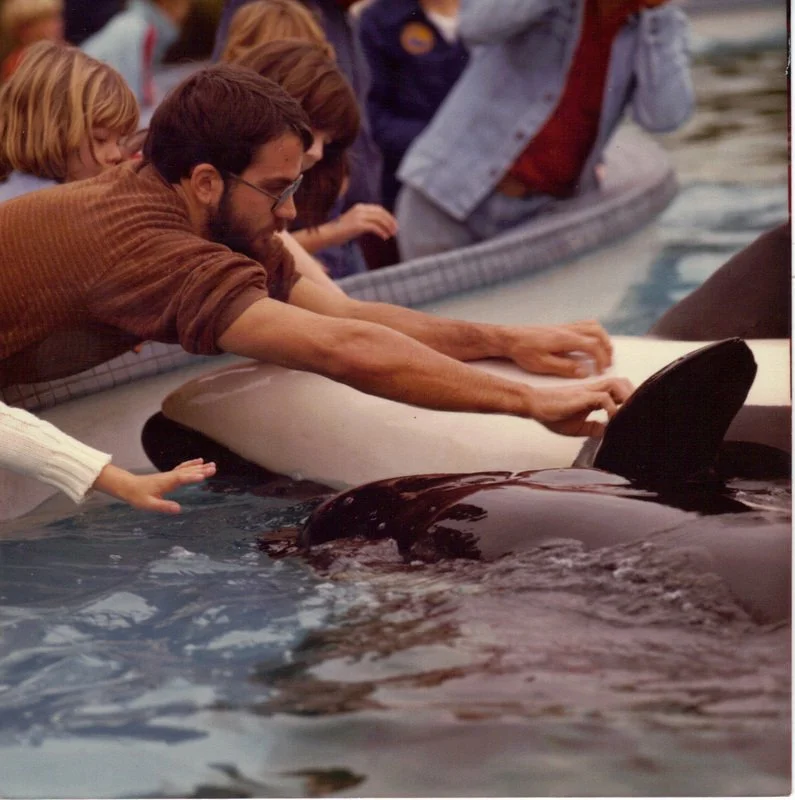

From the archives of Robyn Waayers. The petting pool at SeaWorld San Diego, 1980. Robyn’s brother, Alan Deeley (in orange), reaching down to greet an orca. Alan was also a recognized orca friend.

The Conversation

Robert: A student emailed me about a paper we published in 2016. He had several questions. One stayed with me. What caused aggression toward certain trainers?

I shared my belief. It’s not published and I rarely talk about it.

EE: Which is…?

Robert: The orcas in the petting pool formed genuine relationships, real friendships, with certain visitors who weren’t part of SeaWorld staff. Once they recognized that some humans could understand them, treat them as equals and engage with them, they shared that awareness with each other and with their young. Within that shared understanding, any human who behaved in ways that were demanding, insensitive or unkind was experienced as the opposite of a friend, someone breaking the social bonds of trust they had already established.

Photo: from the archives of visitor “Andy”: Orca leans in, human curiosity reciprocates.

EE: That turns the usual explanation of aggression inside out. We tend to assume adversity, trauma or immediate stress. You’re pointing to something harder to quantify but essential.

Robert: Stress and trauma were certainly present. They always matter. But moral expectation and moral disappointment coexist with them. Reducing orcas only to the effects of environment limits what they can perceive and evaluate.

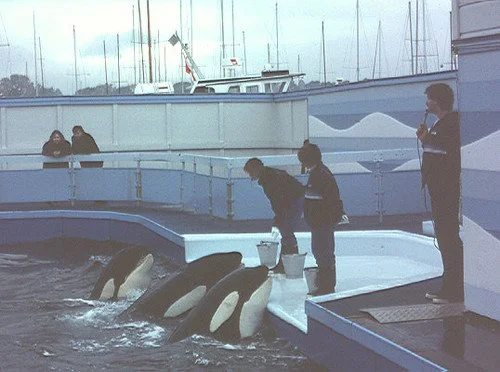

EE: When I look back at the photos of visitors interacting with the petting pool orcas and compare those to orcas with trainers at shows, those buckets of fish created a completely different posture in the humans. Early in my education, positive reinforcement at marine parks was considered humane. Over time, I saw how seemingly gentle methods can still be coercive when the being has no real choice or when what we’re asking of them just doesn’t fit their natural behavior. It’s an ethological mismatch at its core.

Photo: Staff leading a show at SeaLand Marine Park, holding buckets of fish, standing apart with formal, authoritative body language.

Robert: And we don’t think non-humans experience deep disappointment in how they’re treated.

EE: I hear that often: the claim that animals live only in the present. Without the ability to carry forward the past or anticipate the future, a being cannot think with intention.

Robert: Exactly. The orcas I knew lived fully in the present, carried memory and anticipated the future effects of their actions. Their awareness carried all three at once.

EE: Why do you think humans limit the full capacity of non-human animals? “Sentient” is palatable, capable of pain and suffering, but “conscious” seems to cross a line, though it’s self-evident that many non-humans know who they are, where they are and how their decisions affect their families and social groups.

Robert: History and religion perpetuated the dogma that animals exist for human use. It has served us well as apex predators.

Photo credit: Mike Liu, taken at SeaWorld in 2009. Over the years, the shows expanded in scale and spectacle and the expectations placed on the orcas drifted even further from anything ethologically sound.

EE: Critics often accuse observers of anthropomorphism, but there’s an opposite error: anthropodenial, the refusal to acknowledge capacities in non-humans that are clear to anyone who spends time with them. Recognizing intention or morality in orcas isn’t projection. It’s acknowledgment.

From the archives of Russell Hockins, taken during his visits. Russell has long contributed to dolphin research. The photo shows two orcas resting on their backs and one approaching, accepting rubs offered by the visitors beside them. Circa 1980’s.

Robert: Science inherited more dogma than it admits. Bernard DeVoto wrote about this in “Fossil Remnants of the Frontier,” describing his childhood in Ogden, Utah at the boundary between frontier and industrial civilization. He wrote that unless you experience nature first-hand, everything else is “counterfeit—evangelized and sterilized for you.”

Photo by Robert Anderson: Looking from the east side of the Wasatch Range, Utah, where Robert lives. DeVoto would have seen the view from the west. Two individuals, aligned in thought yet separated by time and mountain, connected by the coincidences of life.

EE: Predator and prey categories never sat well with me either. They simplify relationships that are far more fluid. I have prey-like sensitivities - synesthesia, aversion to force - yet I can also tie an aggressor in a mental knot when needed.

Robert: That’s a good use of your human faculties! Humans are poor predators without tools or the labor of other animals. Meanwhile orcas, whom we call apex predators, live in the oceans without degrading the ecosystems. We tend to leave a trail of harm.

EE: Scientific framing contributes to this. We treat the scientific method as synonymous with science. Early scientists were naturalists. They embedded themselves in the lives of the beings they studied. Over time a methodology became a definition.

Robert: Reading about Jane Goodall after her death, I noticed how her methods were glossed over. Her presence within the chimpanzee community was nearly erased to preserve the idea of detached observation. Yet that way of being with them is what allowed her to see so clearly.

Photo: Dr. Jane Goodall at eye level with a baby chimpanzee, each extending a hand toward the other.

EE: Those qualitative methods remain alive in cultural anthropology, anthrozoology and other sciences that recognize rapport as data. Yet skepticism persists, especially in the “hard” sciences.

Robert: Orca studies today are mostly quantitative. Distance is maintained. Instruments stand in for presence. These methods have value, especially where disturbance would be unethical.

EE: They do and they protect wild animals. But quantitative methods tell only part of the story.

Robert: Laws and ethics boards are essential. But there should also be space for scientists to engage when the orcas initiate interaction. They have the cognitive capacity to reach toward us. A recent paper documented thirty-four instances of wild orcas offering fish to humans. They reached toward us with intention. That deserves both scientific attention and ethical openness.

EE: You’ve said that orcas and dolphins are cognitively on par with humans or beyond in certain domains. I’ve asked what gave you that conviction. You’ve lived around many animals and worked with some of the brightest logical and analytical humans in the world. Yet the SeaWorld encounters are the ones that stayed with you. What, at the core, made them different?

Robert: After those visits in 1979 and 1980, I spent decades processing them. I still am. It began at the petting pool. The first orca I met, Canuck 2, approached me on his own, very assertively offering friendship. I was interacting with a dolphin when Canuck 2 made a completely stealth approach. He surfaced from beneath the dolphin and sent them flying backwards through the air with a flick of his head! He slid between my hands and opened wide right in my face. A bit shocking, but I started rubbing and talking to him. On my next visit, Kotar brought me fish presents. Every visit after, whichever orcas were in the pool recognized me by sight and came directly to interact.

EE: That shows recognition and trust. But you’ve experienced that with other animals. What made the orcas different?

Robert: So here is what haunts me. Kotar was barely two years old! He’d experienced trauma during capture and had not grown up within stable orca culture. What affected me was how he invited me to swim and how he went about it.

He let me rub my hand inside his mouth. He slowly began closing down on my hand and forearm giving me every chance to withdraw if I didn’t want to play. A two-year-old with a traumatic past caused by humans recognized my right to consent. Their teeth come in rows with none in the very center, so I moved my hand into that gap. He clamped down and was holding me with pressure from his gums I let him hold my hand. He backed slowly into the pool, pulling me with him. When I resisted, he eased his pressure so my hand slipped free.

From the photo archives of Sylvia Annie Adam: A young orca in transit to a marine park, a moment that completes a journey born of severed family ties and the long miles traveled after being taken from their pod at sea.

At 2,500 pounds he could have pulled me in effortlessly. But he didn’t. That awareness of himself, of me, of consent has stayed with me.

Photo credit: Visitor “Andy,” showing Canuck 2 holding his mouth open in a gesture of trust while a human reaches in to play with his tongue. Circa 1980’s.

EE: What did that moment tell you?

Robert: Two conscious beings met as equals without hierarchy. Kotar had the sensitivity and assurance of an adult human mind. I felt seen. I hope he did too. When two conscious beings meet, analysis isn’t enough.

EE: That’s powerful. Tell me more about what it means to be “fully” seen”.

Robert: It’s about recognizing their full capacity for self-autonomy and expression. Instead of seeing orcas in petting pools as sweet puppies, we can understand them as full beings with the right to express the whole range of their emotional and moral lives, from kindness and empathy to self-preservation and even anger in the face of injustice. There’s a legal advocacy group working on behalf of non-humans whose capacities once seemed reserved for humans.

EE: The Nonhuman Rights Project.

EE: You have a scientific proposal for this kind of work.

Robert: A small group of scientists living on a floating platform, available but not intrusive, engaging only when orcas choose to approach. As Jane Goodall did. The world changed because she entered their world.

I’ve proposed this several times. The responses are polite: boundaries, safety, separation. But we need a place for relational, ethologically grounded studies. What moral concepts might a fully adult orca, free living and having experienced growing up in a wild pod might understand? How would we ever learn without socially interacting with orcas?

Let the orcas initiate the enounters. Let them reveal what they want to reveal. Planned studies would evolve from those early encounters.

EE: You’ve said orcas became aggressive once they realized humans were capable of understanding them - yet sometimes chose not to. The reverse seems true too: your encounters mattered because the orcas recognized you as an equal being. Recognition of that magnitude is rare among humans. No wonder the memory persists.

Robert: That’s true. The petting-pool orcas understood human frailty, my frailty. When beings like that reach toward us, we have an obligation to respond with the best of who we are.

Photo credit, RJ Snowberger: Two orcas in the ocean, at ease in their world, while humans float nearby in a boat.

Conclusion

At the petting pool, a young orca met a young astrophysicist. In that moment they recognized each other as conscious beings.

Robert’s proposal for a small, relational, minimally invasive study offers a way to explore these capacities with consent and ethical boundaries. Supporting such work allows science not only to observe but to enter into genuine relationship with these remarkable beings, revealing minds that challenge our understanding of consciousness and interbeing.

Coda

A final reflection in Tennyson’s words.

But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home.

- from Crossing the Bar by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Photo credit: RJ Snowberger

RESOURCES

Cetacean Culture

To circle back to our first co-authored article: Horses, Orcas and Morality

Orca Network, with sincere appreciation to Howard Garrett, who was featured in Blackfish. A true friend of orcas and humans.

Anderson, R.; Waayers, R.; Knight, A. (2016). Orca Behavior and Subsequent Aggression Associated with Oceanarium Confinement. Animals, 6(8), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani6080049

Anderson, R.; Waayers, R. Center For Humans and Nature: The Other Moral Species

“Testing the Waters: Attempts by Wild Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) to Provision People (Homo sapiens),” by Jared R. Towers, Bay Cetology; Ingrid N. Visser, PhD, Orca Research Trust; and Vanessa Prigollini, MAREA (Marine Education Association). Journal of Comparative Psychology, published online June 30, 2025.

Whitehead, H., Rendell, L. (2015). The Cultural Lives of Whales and Dolphins. University of Chicago Press.

Allen, S. J., Bejder, L., Krützen, M. (2013). Why do dolphins carry sponges? Culture explains tool use in dolphins. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 280, 2011546.

Sargeant, B. L., & Mann, J. (2009). From social learning to culture: intrapopulation variation in bottlenose dolphin tool use. Animal Behaviour, 78, 249–255.

Cross-Generational Teaching & Social Transmission

Rendell, L., & Whitehead, H. (2001). Culture in whales and dolphins. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24, 309–382.

van der Schaar, M. et al. (2025). The role of social transmission in the use of a new behaviour by killer whales in response to fisheries. Animal Behaviour.

Janik, V. M. (2014). Cetacean vocal learning and communication. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 28, 60–65.

Cross-Modal & Sensory Cognition

Pack, A. A., & Herman, L. M. (1995). Sensory integration in dolphins: cross-modal perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 21, 1439–1450.

Soldevilla, M. S. (2020). Echoic and visual integration in toothed whales. Marine Mammal Science, 36, 1302–1321.

Documentary Films

Resident Orca and Her Relatives Beneath the Waves (2025)

The Loneliest Whale: The Search for 52 (trailer)

Intentionality, Innovation & Flexible Cognition

Eskelinen, H. C. et al. (2022). Killer whale innovation: teaching animals to use their creativity upon request. Animal Cognition, 25, 723–736.

Marino, L. (2002). Convergence of complex cognitive abilities in cetaceans and primates. Brain, Behavior and Evolution, 59, 21–32.

Herman, L. M. (2010). What laboratory research has told us about dolphin cognition. International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 23, 310–330.

Physiological and Neuroanatomical Correlates of Cognition

Hof, P. R., & Van der Gucht, E. (2007). Structure of the cerebral cortex in cetaceans and primates. The Anatomical Record, 290, 1111–1122.

Oelschläger, H. H. A., & Oelschläger, J. S. (2002). Brain and sensory systems of the bottlenose dolphin. International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 15, 184–198.

Butti, C. et al. (2009). Neuroanatomical basis of cetacean intelligence. Brain Research Bulletin, 79, 223–235.

Curious to explore the connections between horses, orcas and morality? Reach out to us today. We would love to hear from you and continue the conversation

Mentioned

Crossing the Bar by Alfred, Lord Tennyson - Full

Friendly Reminder: These articles are meant to spark thought, not replace expert guidance. Consult species specific professionals for individual advice.

About the Authors

Robert Anderson, BS, MS, Astrophysics

I’ve always been drawn to non-human animals. In college, I worked on a horse farm and came to know 32 horses as individuals, each with distinct personalities. That experience deepened my appreciation for how complex, and often strikingly similar to human, non-human animal behavior can be. Over the years, I’ve had unforgettable encounters: standing my ground and calmly talking down an angry mother moose, crawling on all fours among a wild flock of Dall sheep, and coming face-to-face with a mountain lion.

In 1979, at the age of 30 and two years out of military service during the Vietnam era, I was deeply influenced by books like Lilly on Dolphins. I set out to answer a question for myself: just how intelligent are dolphins? That quest led not only to profound experiences with dolphins and orcas, but to a lifelong fascination with the minds of other species.

Professionally, I’m a physicist by training and spent the bulk of my career managing the construction of missions in unmanned space exploration. But throughout my life, the exploration of non-human animal intelligence has remained a personal frontier, just as compelling as the cosmos.

Désirée Braganza, EdD, EBQ received her equine behaviorist qualifications from the Natural Animal Centre, located in South Africa. As a member of Bodhi Horse Practice, she collaborates with equine professionals worldwide on research projects specific to experiences of domesticated horses from an ethological lens. She is a horse partner, a rider and has cared for and supported numerous horses over the years. Désirée recently relocated from Northern California and is now based in Monroe, Georgia, USA. She consults internationally in person and virtually.

We believe in making ideas freely available, without paywalls. If this article resonates with you and you’d like to offer your support, feel free to participate in a way that feels true to you. All proceeds will go to the Orca Network.